Six years ago, Paul Schrodt (writing for GQ) lamented the fact that one of his favorite guilty pleasure films, the 1999 sports-drama Game Day starring the late Richard Lewis, was impossible to watch on any streaming platform. (I’m pleased to report that, as of December 2025, he can stream the movie on Amazon for a fee.) Schrodt doesn’t make a case for physical media over streaming subscriptions, but when a film is absent from the now massive digital media library the argument is implicit. Perhaps – and I mean no offense to Game Day, I haven’t see it – not as strongly for less successful, less important films, but certainly for those which are representative of the great American catalog. If you’re under the illusion that your favorite film will always be available with a click or two, the truth is: maybe it isn’t.

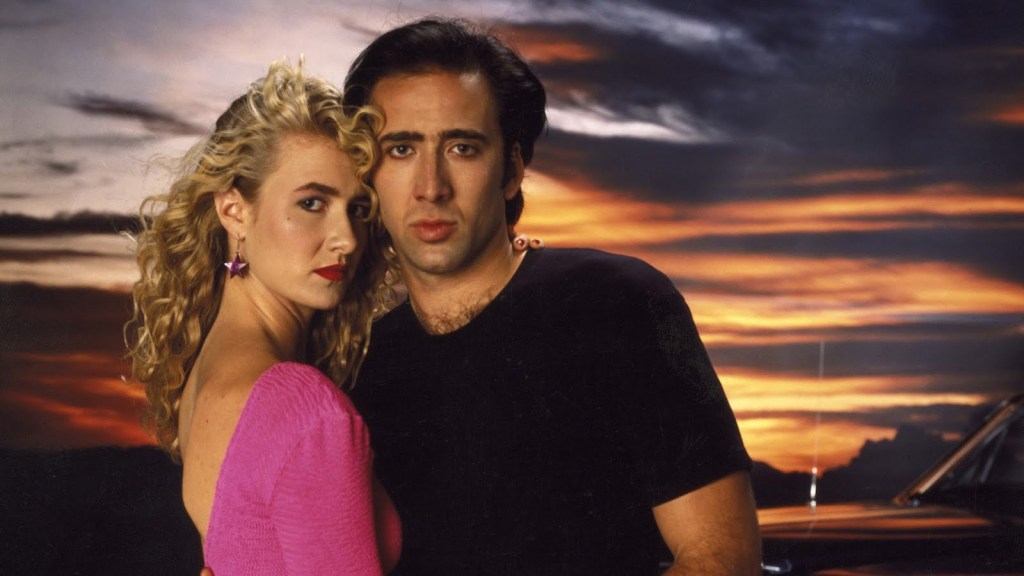

One such film is 1985’s Cocoon. Directed by Ron Howard and released to respectable acclaim and box office success (roughly $56-$57 million), Cocoon was ubiquitous for children of the Reagan/Bush era (myself included). 20th Century released the film on DVD in the early 2000s, and again on the blu-ray format in 2010. The discs quickly sold out, and remain out of print in North America today. Schrodt lists the film along with Kevin Smith’s Dogma, David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, and George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead as a startling example of “big” American films unavailable for streaming on any platform. (In more good news for him – all three are at this time.)

Cocoon, however, remains absent from streamers. In the years since the original blu-ray release, 20th Century has been acquired by Disney, who are not only disinterested in clearing the rights to the film for release, but generally averse to catalog releases and physical media in general. This should come as no surprise; when your business model depends on keeping subscribers engaged, you prioritize new content that will generate larger viewership – and not a 40-year-old film. Ron Howard has remained mute on the subject, though some industry insiders claim that acquiring the rights to James Horner’s score is a major barrier Disney is unwilling to tackle. I find this theory implausible to say the least. Horner’s estate (he died in 2015) has never presented much of a barrier to releasing films that he scored; even the 1983 fantasy flop Krull received a steelbook 4k release just months ago. It seems logical that Horner’s estate would want to capitalize on the film that launched a successful career for the composer, and whose re-release on streaming services and physical media would almost surely lead to further revenue. The issue must be on Disney’s end, not in the Horner corner. I am inclined to believe they’re operating on their “McRib” business model: films are kept in their archives and unavailable in order to capitalize on hype/anticipation, then released in limited quantities and for a limited time. It’s a model they used for their “Disney Movie Club” (which ended in 2024), where members agreed to buy a minimum number of DVDs/blu-rays in exchange for exclusive access to Disney films. Among them, of note, were beloved classics such as The Black Cauldron, The Absent-Minded Professor, and Swiss Family Robinson. No further physical copies of these films have been released; to view them and many more requires a monthly subscription to Disney+.

Recent news that Netflix intends to buy Warner Brothers only increases the anxiety that many academics of film (and serious film “buffs”) feel about the future of movies. It’s perhaps assumed by the general viewing population that eventually all media (print, film, audio) will be accessible digitally and instantly through a streaming service. The curious case of Cocoon and films like it puts that myth to lie. When the home video market arrived in the late seventies and early eighties, it lifted the barrier to access that had existed since the industry’s early years. Historically, all of the arts were an in-person affair. To experience art, one had to be where it was happening or make it oneself. To see a movie meant a trip to the theater, and it was expected more or less to be a one-off thing, unless the film got a re-release or you knew someone with a print and a projector. The printing press had liberated the written word, photography the visual arts, and the phonograph the world of music. Home video, in clunky BETAMAX and more portable forms as the years went on, brought the world’s catalog of films to our fingertips.

We might wonder: was it a better state for the arts, that to “experience” a painting, a song, a film required showing up somewhere? Great dinner conversation perhaps, but at this point Pandora’s box is open and tossed to the floor; we expect immediate and easy access to music, images, prose, and films and there’s no going back. But doesn’t streaming provide precisely this kind of carefree access to films? The answer may require some splitting hairs. It is easy and instant access, but is it gatekeeping in another form to keep the films behind a subscription fee? Further, to tailor the available film catalog to profitability and popularity? A thought experiment here might help. Imagine that you would like to hang Delacroix’s La Liberté guidant le peuple in your house. You can’t afford the original (and the Louvre isn’t lending it out) so you purchase a nice print and put it on your living room wall. It’s now yours to enjoy every day, conceivably, for the rest of your life. Now, imagine that all of the picture frames in your home are digital screens instead, and they’ve stopped making prints of famous paintings. You can see Delacroix’s painting on your digital screen, but it will cost you $17.99 a month. Fail to pay the fee, and your screen goes blank.

This is the heftier argument for retaining media in a physical form. Assuming a respectable durability, a film paid for once on a disc will last its owner a lifetime, to be screened over and again for no additional charge. (There’s also the matter of quality: streaming can’t offer the same lossless audio quality and high bitrate for image quality that a blu-ray can – yet.) In this sense, physical media is by a hair or two the more democratic venue for the film (and other) arts. That physical media is not good business for a streaming service, who relies on monthly subscriptions, is almost a “QED” in favor of it.

The trouble with the Netflix/Warner Brothers merger is it further ensconces the film library behind the doors of those least inclined to make them available in physical form, and leaves smaller, independent films potentially locked away potentially forever. Why release a forgotten but historically significant Cassavettes movie if it won’t amass views/advertising revenue? Presently, we have “boutique” blu-ray manufacturers like Kino Lorber, Arrow, and Criterion who will find, restore, and release some of the most obscure and peculiar films ever made, in part as a service to whatever small cadre of fans the film may have, but also as a commitment to make all of the catalog easily available to public. Without trying to sound like Kino Lorber or Arrow are preservation societies – they aren’t, they’re businesses – these and other companies like them at least recognize the value of film as a medium beyond its financial success (or even artistic acclaim/appeal).

One may suppose this is only a concern for neck-bearded fans of Tammy and the T-Rex and not for mainstream viewers, who are happy with the newest Marvel Studios content and whatever else Disney, Netflix, and Apple puts out. Historicity and fine-grained detail aren’t that important to the average viewer, goes the thinking. Similar statements were made when music went digital: that lossy formats like .mp3 were fine for most listeners and only snobby audiophiles would recalcitrantly cling to their CDs and vinyl, and in any case nobody needs a remastered CD version of MECO’s disco reimagining of the score to The Wizard of OZ.

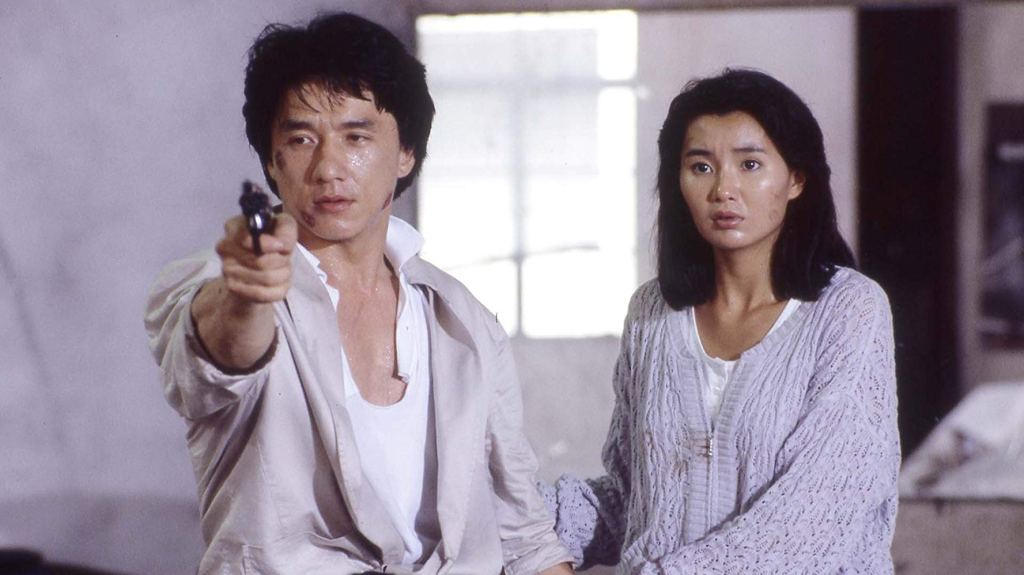

That argument has generally proven true with films, too. If we grant the perspective that art should exist for reasons other than easy consumption any merit, though, physical media is still in the running. Take the previous example of Wild at Heart, the neo-noir film that likely has more fans than Tammy and the T-Rex but isn’t exactly fare for the typical TV watcher. For those who appreciate and study David Lynch’s films, blu-rays offer the best representation of his vision, color graded according to his design, scanned from the best source to the highest quality. The discs also offer a wealth of supplemental material from those who worked on the film, living commentary and reflection that enhances and contextualizes its historical significance. In a sense, a proper physical release of a film recognizes it as more than a piece of candy to be eaten and forgotten, a critical thing when so many films did so much more than entertain: they changed the arts, they inspired political, social, and cultural movements, their images and words became a part of the zeitgeist and are quoted and referenced every day.

Is it fitting that Netflix should own them completely and sell them back to you over and over again? Or, in the curious case of Cocoon, that some movies with substantial impact may just be forgotten and lost?